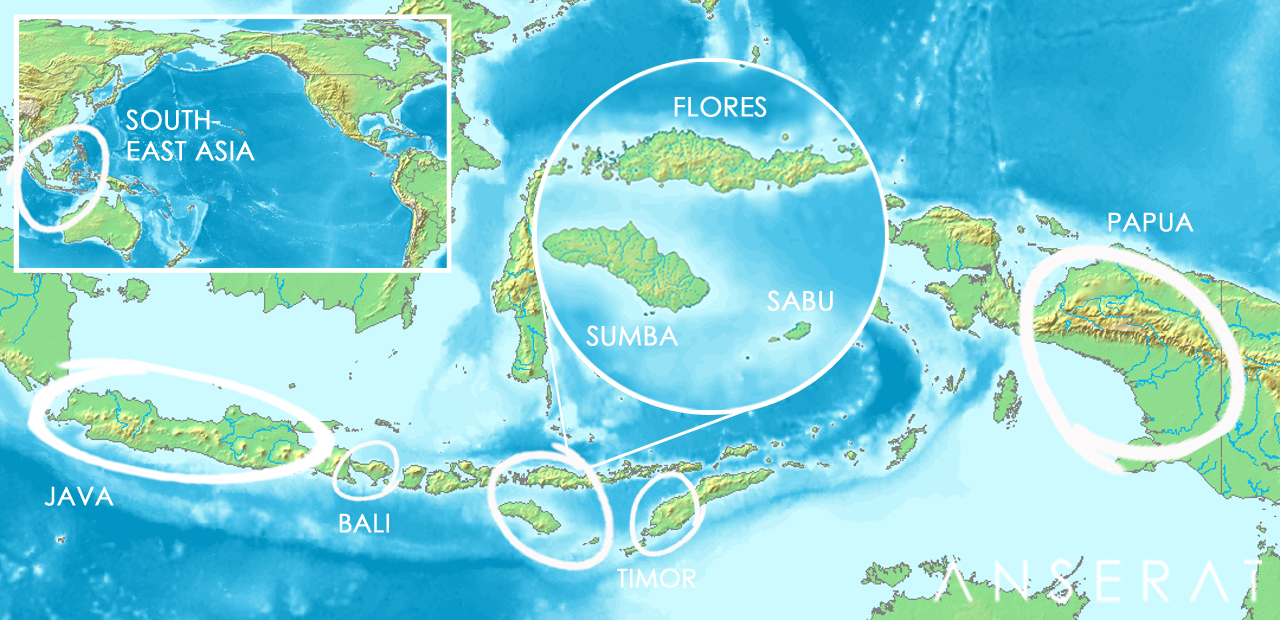

Sabu {or commonly ‘Savu’} is an eeny weeny little island in the Lesser Sunda group, roughly halfway between Sumba and Timor {also comprising two other even smaller islands, but they’re not massively interesting textile-wise}.

It has a very similar history to that of Flores {which I wrote about recently, see here}, except that the Portuguese never set eyes on it, and with the addition of the small matter of the massacre of the crew of a Dutch United East India Company sloop, which ran aground on the island in 1674. In a refreshing break from typical colonial history, the Savunese then managed to whoop the Dutch by withstanding the siege they attempted on the fortified village of Hurati. Eventually the Dutch retreated but then forced the rest of Sabu to pay large fines of gold, beads and slaves. And predictably the Euros eventually managed to get their mitts on the whole island, by signing a number of treaties in 1756.

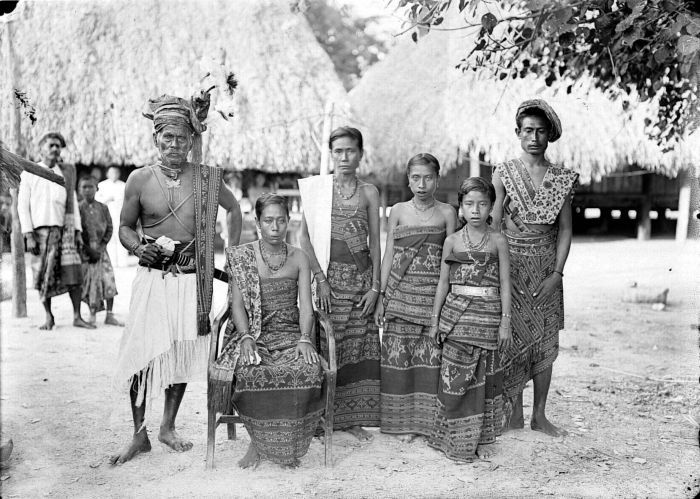

{this is from the Dutch/Indo war in the Molucca Islands but I imagine it looked pretty similar in Sabu}The population of the island consider themselves to be of Aryan Hindu descent, and it is widely believed that the ancestors of the Savunese were 16th century refugees from Java, whose Hindu empire had been squished by Islam, forcing them to emigrate elsewhere. However later on the Dutch missionaries did their usual trick and introduced Protestantism, which remains the religion of the majority today albeit with a traditional animist twist. The current day population certainly look very different to their neighbours on Timor and Sumba.

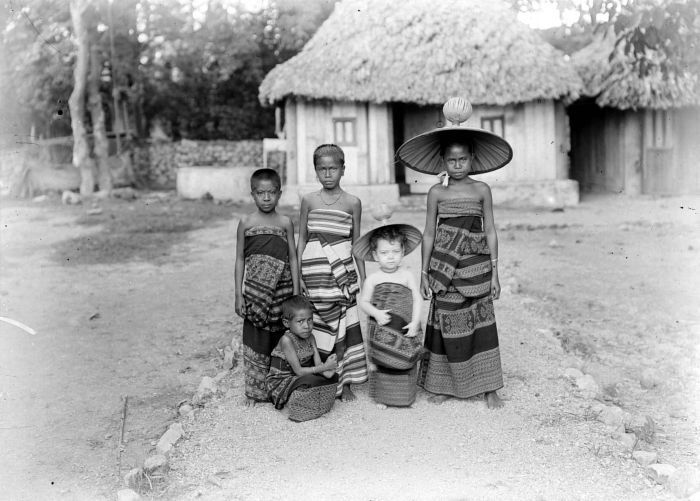

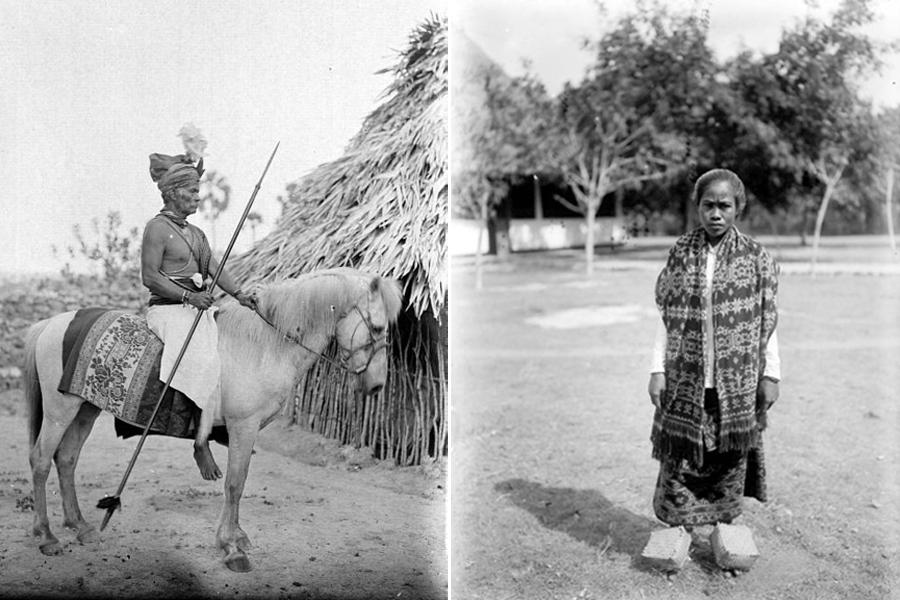

{these incredible images are courtesy of Amsterdam’s Tropenmuseum – see here for more}

The tribal history of the island is pretty interesting, and strongly linked to the ancient religion Jingi tiu. There are two main clans, the Hubi Ae {or ‘Greater Palm Blossom’} and the Hubi Iki {or ‘Lesser Palm Blossom’}, between which inter-marriage was absolutely forbidden until just a few generations ago when the population started to convert to Christianity. Each of the two ‘hubi’ clans are subdivided into various sub-clan ‘wini’ {or ‘seeds’}, and to this day it is still often preferred that a man marries into the same clan as his mother and grandmother, and even within his own wini. It is said that the original split came about a few centuries ago as the result of a pair of sisters, Muji Babo and Lou Babo, with massively oversized competitive natures, who were both determined to prove that they had the best weaving skills and indigo dye recipes in all the land – interesting to see that human nature often remains the same across centuries and continents, haha.

Sorry, digressing…so this relates to ikat weaving in that it is considered extremely poor manners to openly discuss one’s membership of these hubi and wini, so over the years each clan has developed their own weaving styles and motifs to act almost as ID cards, which are passed down through the generations and still adhered to today. The Hubi Ae wear the ‘Ei Raja’ ikats and the Hubi Iki the ‘Ei Ledo’. There is also a third type of ikat the ‘Ei Worapi’ which is considered a free for all option for both clans, but which is never used for ceremonial purposes, only for daily wear.

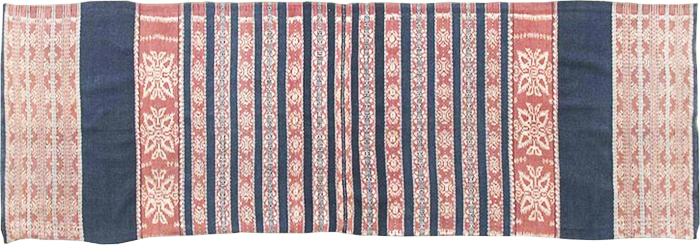

Similar to some of the textiles found in Flores {see here}, Dutch influences can be seen in the ikat motifs, as well as older tribal ones. Generally Sabu textiles have stripes of very dark indigo or black, interspersed with motifs symbolising flora and fauna, as well as various geometric patterns. The colour palettes are usually more restricted than the ikats of other islands, with just blue, black and red as the stars of the show.

Let’s start with the Greater Blossoms. The Ei Raja ikats have a series of narrow stripes on either side of the central seam: seven solid black ones interspersed with six colourful stripes featuring ikat motifs. The wider bands towards the edges of the textile contain larger ikat patterning, and display the wearer’s wini for all the world to see. These main motifs usually feature only two colours, and a common option is the ‘kobe’, which is a king’s betel nut implements {not sure exactly what these are, bear with me, although I have heard that it stems from a traditional legend about a goddess and a kobe-carved treasure chest}.

The Ei Ledo textiles are fairly similar to an untrained eye, but feature only four slightly wider black stripes on either side of the central seam, and accordingly only three colourful ikated ones. The wearer’s wini is again discernible from the larger motifs. As on other islands, the art form developed over time with the introduction of new patterns such as the patola motif {see here for more info}. These motifs were restricted to use by the aristocracy and there are two styles in Sabu: one for the Greaters and one for the Lessers.

It is commonly thought that the Ei Worapi textiles came about as a result of the introduction of Christianity which missionaries pushed onto the local population. The ancient Jingi Tiu religion and traditional clan structure were strongly discouraged by the Dutch, and this new type of ikat with its European-style floral and vegetal forms was a way for women to convert to Christianity and still have something to wear every day. The motifs of the Ei Worapi ikats are very distinct from the other two textiles types, and usually have three or four colours.

These ikats bear a striking resemblance to the textiles of the Sikka and Ende regions of Flores {here for more}, with their motifs inspired by old crochet patterns brought over by the Dutch nuns during colonial times. The Savu Sea was a fairly major trading hub, which explains how these ideas and innovations spread and mingled.

{it seems that it was quite the thing to do to garb one’s Euro sprogs up in trad ikat gear back in the olden days}And now let’s take a look at how these gorgeous textiles are used. As in Sumba and Flores, traditional dress for women is a long ikat tube skirt, or ‘ei’ in Savunese. Historically it was worn from the waist down to the ankles, apart from in formal or ceremonial situations, when it was pulled up to the chest bone and tied at the side {RHS-tied for the living, LHS-tied for the dead}. These days however, most women either wear the tube skirt up top or pair it with a blouse, like these ladies below {also note the what-looks-like batik shoulder cloths, or ‘selandang’}:

Men typically wear a rectangular hip cloth, called a ‘hi’i’, and an ikat selandang. I’ve read that most hi’i are either made of indigo and white in roughly equal parts, or made with three colours like the example below, but all of these Tropenmuseum images show pure white ones, paired with coloured selandang. So not sure what to make of that really.

I do know though that none of the over-zealous competitive fallout affected men’s ikat textiles – the motifs used on the hi’i and selandang do not follow clan lines, unlike those of women’s ei.

For followers of the traditional animist Jingi tiu religion, wives may only weave hi’i textiles for their husbands if they belong to the same wini. If not, one of the wives’ sisters-in-law or mother-in-law has to get out her backstrap loom and do the honours. This rule is often followed even by people who mix a bit of Christianity in with their Jingi tiu.

Another striking point are the burial clothes of the Savunese: in order to help their ancestors find them in the afterlife, people are buried in their specific clan motifs, and in textiles that have been made solely of locally-produced dye pigments and locally-grown cotton. I love that concept.

See here for information on the weaving process and natural dyes used, which are very similar across the different islands of the archipelago. The only difference in Sabu is the source of a couple of the natural dye pigments.

Ooh yes and there’s also a fascinating quirk to the island’s weaving in that after finishing the weaving but prior to sewing the textiles into a tube skirt, a small ceremony is often performed. The Bunga Wurumada {or ‘flower of the delicate eyes’} requires that a chicken is sacrificed in order to cool down the life force of the textile, and thus protect the weaver. Once this has been performed a small zigzag is stitched into the corners of the ikats, usually with rough white thread, to confirm that the correct protocol has been followed.

Unfortunately before learning about this ritual I managed to snip straight through quite a few of them, like a total Textile Buffoon – I’ve managed to rescue a few however, and I love that this small detail of the workmanship will be admired and elevated through framing.

We managed to get our mitts on a select few vintage sarongs from Sabu for our first collection, which have been transformed into gorgeous ikat pillows and framed artwork. Make sure you stop by in early 2015 for a peek!

{credits: Anserai / Tropenmuseum / Indonesia Travelling Guide}

COPYRIGHT Anserai 2014