The islands of Timor, Sumba and Flores are towards the east end of the long chain of beaches, paddies, volcanoes and coral reefs that make up the Indonesian archipelago.

I’ve written about them all before (see here for Timor / Sumba / Flores) in the context of their incredible buna/ikat/ikaaaat textiles respectively, but today I wanted to take a look at the fascinating wooden tribal statues that also come out of these islands.

The various ancient animist religions of the region all honour the spirits of the ancestors, as well as the spirits of nature, a waterfall or a rock for instance. The European colonialists did their very very very best to wipe out these ‘heathen’ religions but they still exist to this day {I am happy to report}, albeit often with a Protestant or Catholic twist. So people still believe that their ancestors’ spirits have the power to help or harm the living, and behave accordingly.

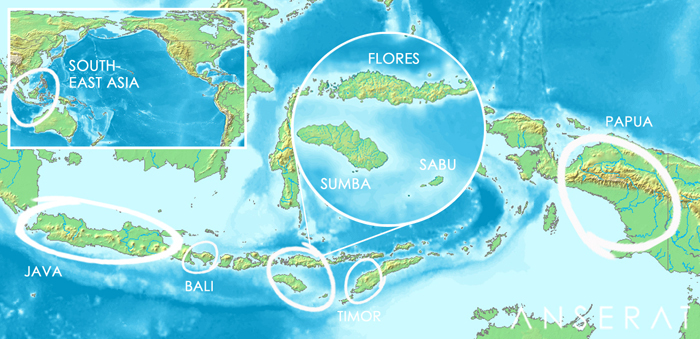

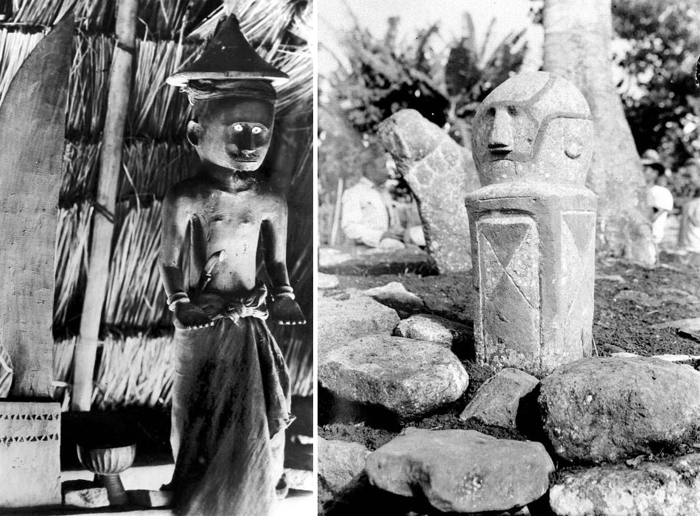

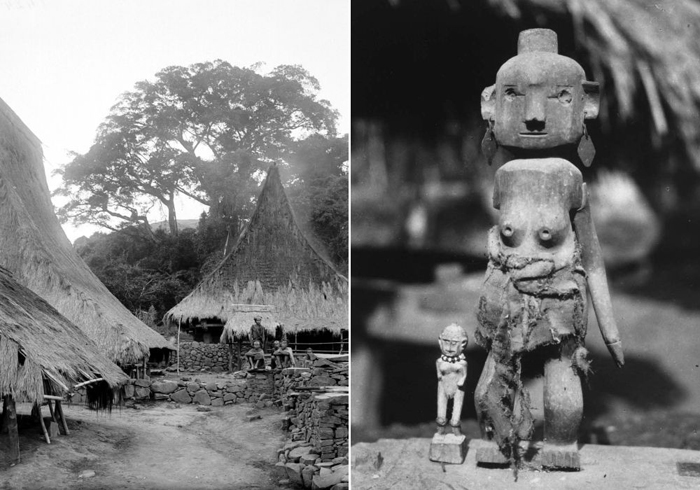

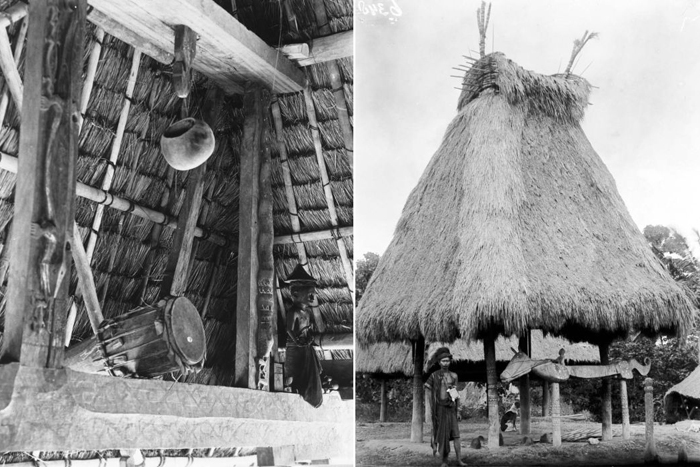

{these incredible images are courtesy of Amsterdam’s Tropenmuseum – thank you Tropenmuseum!}

Wooden and stone tribal statues have been created and worshipped for centuries, as they are believed to be a medium to the world of these spirits, and a means for the living to communicate with their forebears to ask for protection, healing, good health and good fortune. Fertility is also a common theme – any statue with overtly nakeybums bits and pieces is usually created with it in mind, like the female one above right.

And according to what I’ve read this statue below right could either symbolise a prayer for fertility, or the relationship between the ancestors (big’un) and the living (littl’un). Or maybe both at the same time…yep let’s go with that.

So let’s start off with Timor. Animist practices {particularly ancestor worship} are still very prevalent in various parts of the island, both in the Indo half and in the country Timor-Leste. People believe that the spirits of their ancestors live on Matebian Mountain, or the ‘Mountain of the Souls of the Dead’, the second- {or third-, depending on what document you are reading} highest peak on the island.

This deep respect for the ancestors is portrayed through the various styles of statues used in Timor, as well as carved wooden masks. They are used in traditional ceremonies and healing/protection rituals by religious leaders and dancers. They are also placed inside people’s huts above the front door, ensuring that only those with good hearts and positive intent can enter – all baddies have to stay outside. I might do this at home ha, think I will actually.

One really interesting aspect of the Timorese statues is the focus on dual concepts, of pairs of opposites: the living and the dead, the old and the young, and most importantly the male and the female. It is very common to see pairs of tribal statues, a bloke and his lady {like this happy couple above}, rather like Chinese guardian lions {or ‘foo dogs’}, or Philippine Bulul statues.

Moving onto Sumba now, where the ‘Marapu’ {or ‘Merapu’} religion is still very widespread. According to their beliefs, the spirits of the dead move into the ‘heaven’ of Prai Marapu, from where they continue to watch over the living.

In order to keep a stable and peaceful relationship with this spirit world, various ceremonies and rituals are required throughout the year {to restore harmony to the natural environment, which is unbalanced by man’s activities}. If the ancestors are satisfied they reward the living with good harvests, health, protection and prosperity. But if the living break any of the rules {the ‘nuku-hara’} the balance between nature and man becomes unstable and their descendants will be punished.

It’s similar in some ways to the ‘Hungry Ghost’ ceremonies that take place here in Singapore every summer – I love this concept, a way of remembering and honouring your ancestors. Oh and the ‘Día de los Muertos’ in Mexico too. Huh, interesting, it’s all over the place.

Anyhoo, so the statues are carved either standing upright or sitting down, and often have their arms crossed and clasped to their knees or to their hips, like this chap above right.

Most of these statues are placed on stone altars, where offerings are given, but they are also used to mark and protect property, either inside huts, on roof lines or on boundary lines facing outwards {in order to frighten off any evil lurking around the place}.

Moving onto Flores now, where in addition to the statues, totemic structures and megalithic stones are also very common, and relate to the protection given to villages by their ancestors.

I think each village has its own ‘ghost house’, where the people perform their ceremonies and rituals – above is the interior and exterior of one, with what looks like a statue of an ever-important horse figure. As in Timor and Sumba, statues are also kept inside the home or by the front door of the hut, to protect against evil spirits and illness.

Here at Anserai we’ve got hold of a gorgeous selection of contemporary pieces {modelled on antique statues}, in various wood colours and finishes and in different carving styles – go take a peek at our website for more info!

{credits: Anserai / Tropenmuseum}

COPYRIGHT ANSERAI 2014