The origins of the songket weaving technique seem to be a little murky and mysterious, with a few different theories about when and where exactly it evolved. I’ve picked the one I like best to write about here – not exactly a scientific process but I’m the boss in this little corner of the internet, ha.

From what I’ve read it seems to be that trade between China and India hundreds and hundreds of years ago created the marriage of Chinese silk with Indian gold-/silver-wrapped thread, from which the beautiful songket textiles were born.

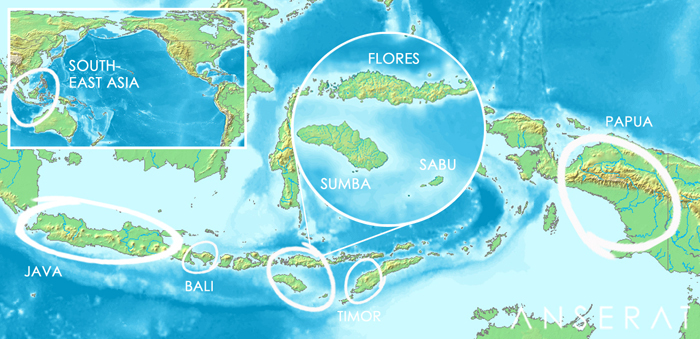

The technique was {maybe} first developed in Mughal India around the 14th/15th centuries, and was introduced to the coastal Muslim sultanates in Indonesia by Indian and Arab traders in the 15th/16th centuries. Palembang and Minangkabau in Sumatra {the biggie island to the left – err…west – of Java in the map below} are to this day famous songket production centres. Traditionally the embroidery thread used was coated in real gold leaf, which meant that only wealthy kingdoms could produce the goodies – it’s closely linked with Srivijaya, a powerful maritime trading empire based out of Sumatra.

In ancient times the songkets of Sumatra were so renowned they were traded far and wide, from China and India to Arabia. The gold mines located in the Jambi and Minangkabau highlands provided the bling, indeed the whole island was once called ‘Swarnadwipa’, or ‘Island of Gold’.

Songkets and kain limar textiles {ikat panels framed in songket} were a status symbol for the rulers of the empire and, apart from the cost being prohibitive for your average joe, there was a strong taboo on their production/use outside the lucky few who counted themselves higher ranking nobles.

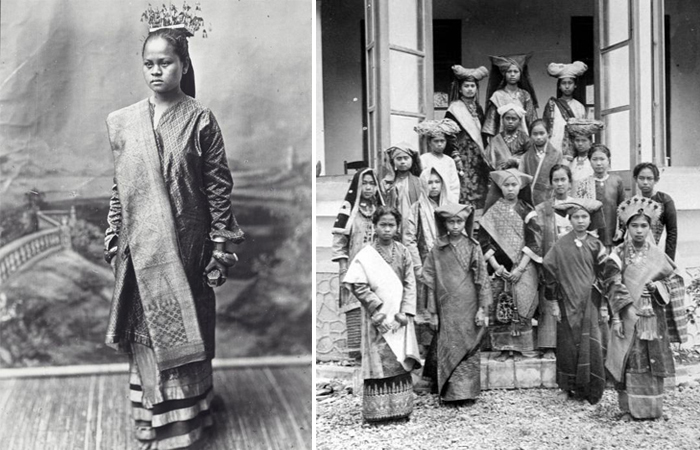

These amazing old pics are from Minangkabau in Sumatra – note the headscarves worn in the Muslim enclaves of the island:

{these incredible images are courtesy of Amsterdam’s Tropenmuseum}

However as with the ikat industries in Sumba, Flores and Sabu, the meddling Dutch colonialists’ sticky fingers also had an impact on the songket trade.

The various Sumatran tribes were plucky fighters, and resisted the Dutch for longer than most of their fellow archipelago-ans {that’s not a word…} but in 1863, after three failed attempts, the Dutchies finally got hold of the offshore island of Nias and other regions followed as they formed treaties and alliances with competing factions.

Because of the disruptions and changes brought about by the Dutch {and presumably because they were nicking all the gold}, for a long period the production of songket suffered from a severe lack of raw materials . In some villages, it’s said that people even removed the gold-wrapped threads from old pieces where the silk ground had started to rot, to recycle them into new textiles.

{Yeh, they were totally nicking all the gold…}

Then, to add insult to injury to these poor songkets, once the Dutch were eventually driven out in the 1940s, the life, traditions and ‘adat’ {inherited wisdom} of the island had been turned upside down to such an extent that the traditional Sumatran rulers totally lost their privileges and protection, and the taboo on ‘commoners’ owning and wearing songkets evaporated into thin air – any landowner’s or merchant’s wife was permitted to add a songket or kain limar textile or three to her wardrobe. Maybe that’s a good thing actually, the old feudal system wasn’t fun for many people…

Anyhoo, check out these lovely ladies below:

{Also note the awesome buffalo-horn headdresses above right, cool huh? They are a part of the traditional Minangkabau ethnic identity}

From its introduction into the archipelago in Sumatra, the songket technique slowly spread eastwards and is now also produced in Bali, Lombok, Bangka, Kalimantan, Sulawesi and Sumbawa. The ones we’ve got our mitts on, here at Anserai, are from the central highlands of Bali. Loads and loads of songket fabric is produced there, but it’s the vintage songket wedding belts that caught my eye {more below}.

The main production area in Bali these days is in the Klungkung regency. In the 17th century the Balinese royalty moved to this beautiful fertile spot, along with all their artisans, and the traditional techniques have survived to this day.

Dancing plays a huge role in Bali’s many many ceremonies and songket textiles are the bling of choice. They’ve also always been used in weddings, but I can’t find any old pics of this sadly, would love to see it.

As in Sumatra, the textiles were restricted to the nobility – the more intricate and well-made the piece, the higher the person’s rank.

The colonial powers also left their mark in Bali. During the Second World War under the Japanese occupation of the island, the Balinese were banned from weaving. The occupiers apparently removed their threads and their looms, attempting to destroy their traditional know-how and cultural history, but the women of the island continued to weave in secret, sneaky-like.

‘So what exactly is this magical bling textile?’, I hear you ask.

Songket is a hand-woven embroidery/brocade textile, in which gold- or silver-wrapped threads pattern a silk or cotton ground textile, in a technique known as supplementary weft {sort of similar to the Timorese buna textiles I wrote about recently, but with gold embroidery}. The shimmering effect of the metallic threads is extremely dramatic, especially in the Balinese sunshine!

The name evolved from the old Musi {ancient Malay} word ‘sungkit’, which means ‘to hook’, alluding to the method of raising groups of warp threads in the ground textile, to slip in the metal supplementary threads.

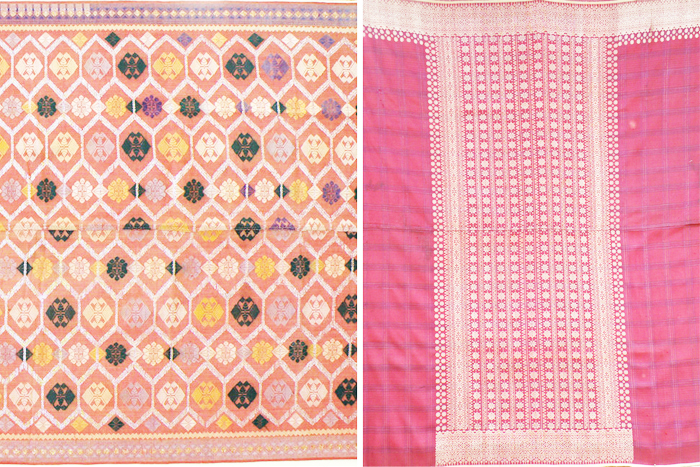

{This is a kain limar on the left above – SO beautiful, those colours!}

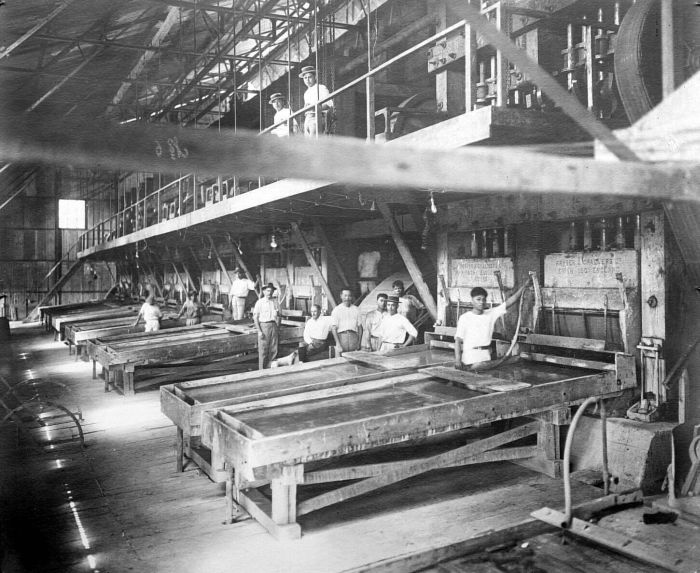

The cotton/silk plain weave ground textiles are stretched over a frame loom {in West Sumatra} or a back-strap loom {in Bali and south Sumatra}, and then a really flat needle is used to raise the warp threads.

In ancient times, silk or cotton threads were coated in real gold leaf, by dangling them in heated molten gold. These days I think it might be brass that’s used, but can’t be 100% sure. The coloured threads used in the ground textile used to be white threads bought and dyed by the weavers, but now they seem to take a mini shortcut by sourcing pre-coloured threads – can’t blame them really: even without dyeing their threads a songket textile can take up to four months to create.

The task of weaving these beauties is usually done as a part-time job by youngish girls – they apparently learn ‘via osmosis’, starting out preparing the silk threads from a young age, and gradually working up from there. By the time they are 20 years old, they are ready to start weaving. It is said that the task cultivates the virtues of patience, diligence and care. Not only that actually, in Minangkabau often the motifs used symbolised Sumatran proverbs that taught proper behaviour. Serious stuff!

A fascinating part of songket’s evolution is the motifs that are used in different parts of the archipelago. In Islamic Sumatra where the religion prohibited the depiction of living beings, the designs were always geometric, patola-inspired, or the forbidden figures of people/animals {gasp!} but stylised so far as to make them unrecognisable.

I’ve read that particular shapes symbolise specific things: circles are the nature of the all-knowing God, rectangles are the four companions of the Prophet Muhammed, diamonds are God the merciful, pentagons are the pillars of Islam and hexagons are the pillars of faith. Each sultan also had his own set of personal motifs, with associated philosophical meanings and prayers.

And like with ikats further east, once the foreigners rocked up the Sumatran weavers started using Dutch designs {although I have not been able to find any examples frustratingly}.

In contrast, in Hindu Bali the textiles were always full of flora and fauna: common animals were ants, ducks, bees, quails, snakes and dragons; and botanicals like flowers, twisted leaves, trees and creepers were common. Traditional Balinese shadow puppet figures and characters from old Hindu epics were also typical.

I think Islam arrived in Lombok after the songket technique, so that island’s motifs started out full of animist and Hindu humans, flora and fauna, but suddenly switched to geometrics with the encroachment of Islam. Interesting, huh?

You can see some of these largely geometric motifs in our wedding belt massacre shot below. It took nerves of steel to snip up those gorgeous old textiles – they are being given a better life proudly displayed on our linen pillows though.

Traditionally songket textiles were only worn at the courts of the Sumatran kingdoms and by Balinese nobility. A long songket skirt was gathered together by a belt, and a ‘breast-cloth’ was wrapped tightly around the torso, sometimes draping over one arm. Loose shoulder sashes were also common {see the Sumatran pics at the top of this post}.

These days however, the textile is more accessible, and most women wear it on their wedding days. It’s not possible to wash the textile {as the metallic threads are so delicate} so people generally keep them for special occasions as opposed to wearing them every day.

In Bali in addition to donning songkets for wedding ceremonies, they are also used for the Hindu filing teeth, the three month and the six month baby celebrations.

And here are a couple of modern day pics, that show the full beauty of these incredible textiles. I think the lady on the right hand side is using a songket wedding belt to hold her skirts together {peaking out behind her fan}. Just stunning, no?

Here at Anserai we’re the proud owners of a gorgeous selection of vintage gold and silver Balinese songket wedding belts, after sorting through piles and piles and piles of the blighters.

I’ve never seen these being made new, so think the supply of old ones might be slowly running out…this is making me want to hop on over there and buy them all up – if there’s no blog post published here next week you’ll know where I am.

Added to delectable 100% natural linen pillows, these songket wedding belts really steal the limelight and add depth {see below centre on the sofa}, the perfect addition to a pillow vignette. Coming to our online boutique soon!

{credits: Anserai / Tropenmuseum / Wikimedia Commons}

COPYRIGHT Anserai 2014