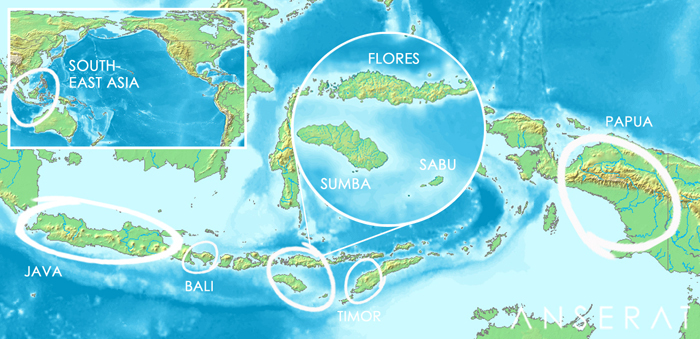

The island of Timor is one of the major landmasses of East Nusa Tenggara, poking out of the Savu Sea between the Solor Archipelago and Australia.

Similar to Papua {which I wrote about recently, see here}, it is split slap bang right down the middle, into the very young country Timor-Leste {or ‘Timor Timur’ – which confusingly means ‘East East’} on the errr east, and the Indonesian province of West Timor {‘Timor Barat’}.

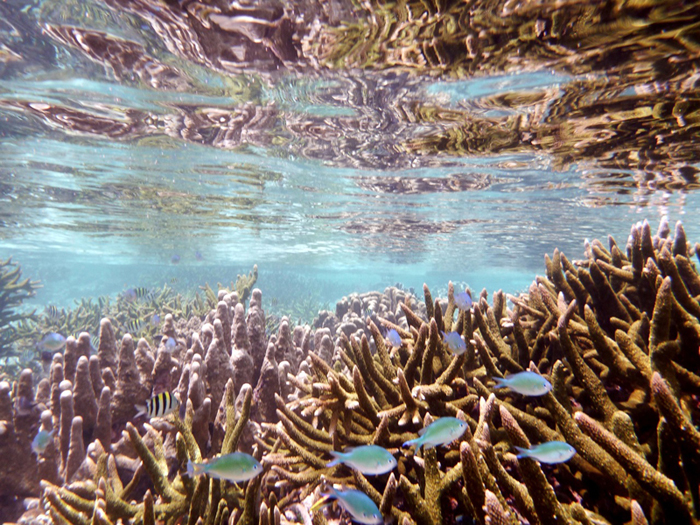

Indonesia’s long long line of volcanoes bypass this island, and head northwards passing through the Moluccas, but its landscape is still very dramatic both above sea level…

…and below it:

From the 14th century onwards Chinese, Indian and Javanese traders popped into Timor for their fix of honey, beeswax and sandalwood. In fact it’s said that the reason there are so many horses in Sumba {which I also wrote about recently, see here} is that the Indian merchants brought them from Arabia to trade for this precious aromatic wood.

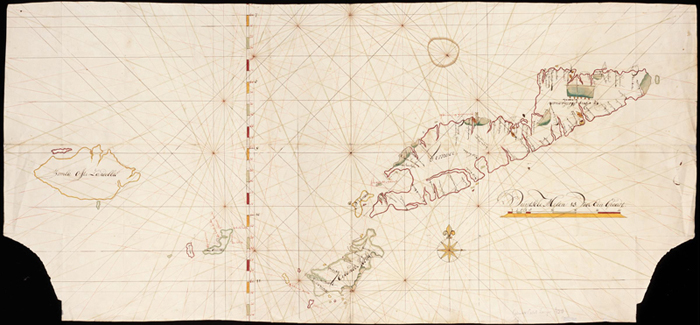

The Portuguese eventually got wind of these natural resources and joined the party in 1515. They first nicked a small portion of the island on the northwestern coast {now called ‘Oecussi-Ambeno’}, and then managed to get hold of the whole eastern half of the island which they held onto for over four hundred years. Then those ubiquitous Dutchies were at it again and settled the western half of the island in 1640. I suspect the two sides were not besties, think they basically scrapped over ownership for the next few centuries until the border was formally agreed on in 1914. Both sides also did their usual trick of converting as many people as they could to Catholicism or Protestantism, depending on which half of the island they happened to call home.

Portugal had a pretty major revolution in 1974, got rid of its nasty dictator and decided that its colonies should really be given their land back after, you know, a piffling four centuries or so. So East Timor {including the funny little enclave of Oecussi-Ambeno} became its own sovereign nation very briefly before Indo invaded in 1975 and started calling it ‘Tim-Tim’. The East Timorese were pretty unimpressed {that name is enough to annoy anybody I imagine…} and proceeded to rebel for the next 25 years {actually I should not make light of this, it was all pretty nasty from what I can gather} until full independence was granted in 2002 and it became known as Timor-Leste. So it really is a very young country, just a teenage tiddler.

Compared to this the West Timorese had it pretty easy. In 1949 ‘Dutch Timor’ just became part of greater Indonesia when it became independent under Suharto.

I find it so fascinating that the reverberations of the Euro colonialists’ meddling all those years ago were still being felt in 2002. Crazy.

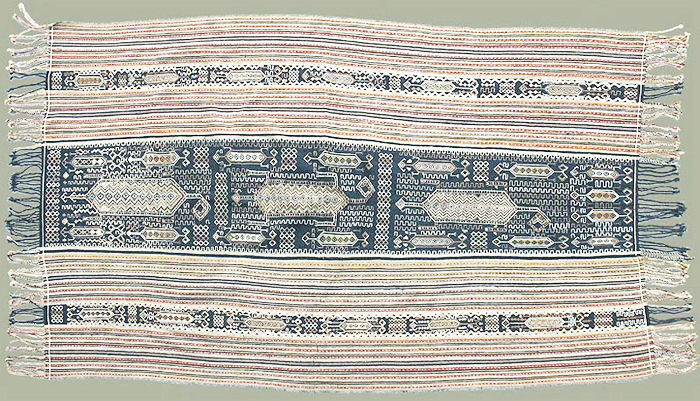

Anyhoo, so onto the textiles. I shall cover Timorese ikats in a future post but today I wanted to discuss the fun bright weaving technique that is ‘buna’, coming out of West Timor.

It looks sort of like embroidery, but instead of being added to a pre-finished textile, it is actually woven into it. As you can see in the pic below, on a backstrap loom a plain colour warp thread is combined with short colourful supplementary weft threads, which are wrapped around groups of the warpies. It can take up to 18 months to create one of these beauties as each thread must be tucked into the body of the textile so that it’s invisible.

As you can see in the examples below, buna is usually combined with other weaving techniques in the same textiles, most commonly with ikats and also often with ‘sotis’, which is a floating warp sort of shizzle I believe.

The buna technique was traditionally just practiced by aristocratic chicks. Silk cloth and thread imported from China were exclusively used back in the day, and these upper class ladies were the only people who had the funds to purchase it and also the contacts needed to source it from the Chinese traders {as their blokes were the people who generally brokered trade deals between the foreigners and the Timorese}. And also they were the only people with enough spare time on their hands to make these intricate pieces. So in the olden days the social status of a lady was indicated by the quantity of buna textiles on her frocks – any more than three rows meant serious wedge.

Generally synthetic dyes are used for buna, and have been for a long time, unlike our vintage ikats that are made purely using vegetable and mineral pigments. However occasionally you do see a very old specimen featuring naturally dyed threads, which are always really rather beautiful {see above}. The large motifs in this textile are stylised lizards {or crocs} with curled tails, and the wiggly lines around them symbolise water.

Other common motifs are fish, ancestors, geckos, praying mantis’ and frogs. Stylised geometric motifs are also very common, such as hooked lozenges {or ‘kaifs’}, concentric diamonds and zigzag borders. Because of the meddling missionaries back in the day, in many areas of the island people have abandoned their traditional animist motifs, which I find really really tragic.

In the example above a kaif ikat motif is combined with a central panel of buna featuring a similar diamond geometric motif, and two borders running along each edge. Such stunning colours and striking patterns!

And here are some of the contemporary motifs and palettes available – they’re bright and fun but just don’t compare to our beautiful vintage ones!

I’ll talk about the traditional Timorese tube skirts and blankets in my ikat post, but I wanted to mention the awesome naisa technique as I think it maybe inspired the design of the buna goodies we have here at Anserai.

Naisa weaving is a tapestry-like style, which is sadly becoming more and more rare in Timor. It is often applied to men’s ‘futu belts’ which were worn back in the day for ceremonies – you can see a narrow white one on this chap below:

The thing that’s interesting about this technique is that the naisa tapestry sections are often decorated with bling such as shells, bells, beads or antique Netherlands East Indies coins, rather like the tribal bags we have managed to get our mitts on.

Our small yet perfectly formed selection of really unique and intricate tribal bags are made out of vintage buna textiles, wooden beads, cotton tassels, colourful trade beads and antique beautifully-patinated Netherlands East Indies Guilder coins.

There aren’t many of them though, better get your skates on if you fancy one!

{credits: Anserai / Tropenmuseum / Wikimedia Commons / Indonesia Travelling Guide}

COPYRIGHT Anserai 2014